Supporting Native Bees in Your Landscape with Locally Sourced Native Plants

By Natasha Stairs

Spring is on the horizon! Each day the sun grows stronger and rises higher in the sky. There is a feeling of lightness all around. As the pussy willows emerge and the soil warms, I begin to look and listen for the new queen bumble bees that need those very early sources of pollen and nectar to sustain themselves after a long winter in hibernation.

Not everyone has the space or conditions to grow a willow in their backyard, and only a few native species are suitable for urban gardens, but if you are able to, the early bees will thank you. They have to make do with non-native haskap bushes in my garden, but they don’t seem to mind as the bushes are abuzz with activity as soon as the first flowers appear early in May.

Bombus centralis on Great Northern Aster

Photo credit: Manna Parseyan

I add more locally sourced native plants to my small urban garden every year because they are optimal sources of food for the local native bees. Some bees emerge only when their preferred flowers bloom, and many native flowers are programmed to bloom when the actively foraging bees need nectar and pollen. These native plants provide the bees with the right nutrients at the right time of year, and even at the right time of day. Factors such as flower shape, size, colour, and odour determine how and when the plant is visited by the bees. This relationship is long-standing and cannot be wholly replaced by a cultivar of a native plant, much less by an imported one.

That said, don’t start ripping out all the cultivars and non-native plants in your yard! Many do provide good supplemental sources of pollen and nectar, and perhaps even shelter, for the native bees. Take some time to observe which plants the bees visit the most and keep those. However, if you have plants that you have never liked, or that are not thriving, consider replacing them with some locally sourced native ones. There is a well-behaved native plant suitable for just about every growing condition in a garden.

Why the emphasis on locally sourced seeds and plants? A seed is a seed, isn’t it? Not exactly. For example, Gaillardia aristata, or Blanket Flower, is native throughout Alberta and most of Canada and the US. Consider that the conditions in which Gaillardia grows in Lethbridge are very different from those in Edmonton. Although they may be the same species, plants grown from seeds collected in the grasslands of southern Alberta have evolved to survive in hotter, windier, drier conditions than those of the boreal forest and parkland regions to the north.

Factors such as heat, humidity, soil, and even daylight hours may affect a plant’s ability to thrive and to produce adequate levels of pollen and nectar. One of the great things about growing locally sourced native plants is that once established, they can handle whatever Mother Nature throws at them because they have evolved over the course of millennia to survive in those very conditions.

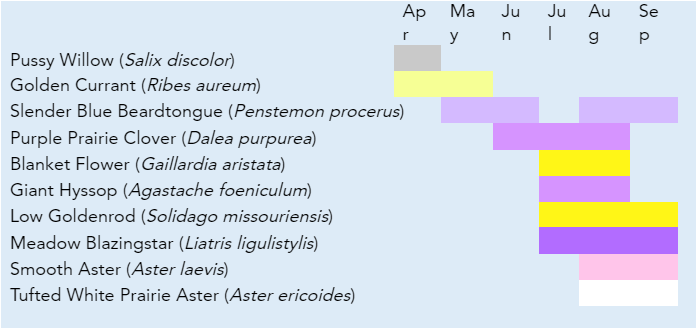

So, where to begin? Look at the flowering plants in your garden and determine what blooms when, and for how long. Make note of the flowers that the bees visit most often. Bees are active from early spring through to the fall, which is why it is important to have bee-friendly blooms throughout the entire season. Native bees don’t travel far from their nests, so the greater the variety of flowers with overlapping bloom times you can provide, the better. Landscapes with low plant diversity have the potential to create a feast or famine scenario for native bees.

A simple way to track bloom times in your garden is to make a chart like this.

Planting species together in clumps of 5 to 7 plants, or in large drifts of 1m2, gives the bees big targets to aim for. More importantly, the close proximity of plants to each other and to nesting sites means that the bees can expend less energy on foraging and more time on ensuring there will be an abundant and healthy next generation.

The list below has examples of high reward nectar and pollen plants that grow in most regions of Alberta, but it is not a definitive one. There are many other native flowering plants that are also of value to native bees.

Wildflowers

Blanket Flower (Gaillardia aristata) attracts a wide variety of bee species. Leafcutters and green metallic sweat bees are often found on these plants. Likes sun and poor soil but will grow in just about any well-drained conditions.

Giant Hyssop (Agastache foeniculum) is a high reward plant that attracts a wide variety of bees. A good starter plant as it is easy to grow and is not fussy about soil conditions. Sun/part shade.

Goldenrods (Solidago spp.) are sources of very important late-season pollen which is used by late-nesting bees to provision their nests. Attracts a number of specialist bees. Need sun but are generally not fussy about soil and moisture levels.

Meadow Blazingstar (Liatris ligulistylis) is a pollinator magnet. Both long- and short-tongued bumble bees frequent this plant. Likes sun and any kind of well-drained soil except heavy clay.

Penstemons (Penstemon spp.) are native bee magnets. You may be able to extend the flowering period into September if you remove the spent blooms at the end of first flowering.

Purple Prairie clover (Dalea purpurea) attracts bumble bees and polyester bees. Needs sun and well-drained soil.

Silvery Lupine (Lupinus argenteus) is an excellent source of pollen. Lupines attract bumble bees and mason bees. They need sun and well-drained soil.

Sunflowers (Helianthus spp.) are very good sources of pollen and nectar. They attract a wide variety of bees and are generally not too fussy about soil conditions, but they do need full sun.

Tufted White Prairie Aster (Aster ericoides) and all asters are important late-fall food sources, especially for new bumble bee queens that need reserves of energy for winter dormancy. Asters like sun and tend not to be too fussy about type of soil conditions.

Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa) attracts a wide variety of bees. Likes sun, isn’t fussy about soil, but needs moisture.

Bombus centralis on Common Tall Sunflower

Photo credit: Manna Parseyan

Bombus centralis on Meadow Blazingstar.

Photo credit: Natasha Stairs

Shrubs and Trees

Golden Currant (Ribes aureum) flowers are an important early nectar source.

Kinnikinnik (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi) attracts a wide variety of bees and is an excellent source of nectar.

Wild Red Raspberry (Rubus idaeus) flowers are good sources of nectar. Stems provide habitat for some bees.

Saskatoon (Amelanchier alnifolia) is another excellent choice to support early bees. They flower late May to early June.

Wild Rose (Rosa acicularis) is a very good pollen source but is not particularly useful for nectar.

Willows (Salix spp.) offer the first available pollen to the early bees.

Bumble ternarius on Barratt’s Willow

Photo credit: Patsy Cotterill

Always research plants before buying to ensure that you select varieties endemic to your area and that are appropriate for your growing conditions. An urban gardener will need to consider suckering habits more than an acreage dweller, but that can often be dealt with by installing some kind of buried border.

Supporting native bees in your landscape requires just a little more than the right plants. First and foremost, the habitat must be protected, as best you can, from pesticides, including organic ones. Create buffer zones with fences, trees, shrubs and grasses where possible and avoid purchasing any plants that may have been treated with pesticides, especially neonicotinoids. If in doubt, ask. Your best bet is to purchase native plants and seeds from the most local grower you can find.

Native bees need a messier space than perhaps we humans would like. A few small areas of undisturbed bare ground, preferably in sunny spots, are prime real estate for ground-nesting bees. Hollow-stemmed plants, or those with pithy stems such as raspberry canes and sunflowers are home to some bees, so don’t cut them down in the fall. Wait until the weather warms up in the spring before cutting and leave the cut stems on the ground in case there are any unhatched pupae remaining inside.

Instructions for building your own bumble bee boxes are available on the Alberta Native Bee Council (ANBC) website. These are simple to construct and easy to maintain. Commercially available bee hotels are attractive, but they can be problematic and will require regular maintenance to prevent disease. The best option is to provide some rotting wood, a brush pile, and undisturbed areas of your garden for the bees to find a home in.

Bombus centralis on Wild Blue Flax

Photo credit: Manna Parseyan

Mimicking nature in your landscape by leaving plant matter undisturbed year-round is an excellent way to encourage a wide variety of native bees and other beneficial insects to move in. Diseased materials should always be removed, bagged, and put into the garbage, but contrary to general garden lore, flowerbeds and gardens do not need to be thoroughly cleaned up every fall and spring. I disturbed a sleepy and consequently irritated bumble bee late one autumn when I was cleaning up some leaf litter and mulch. I have done minimal clean-up of my garden beds since then.

And last, but not least, don’t forget to look beyond your fences. Neighbours and municipal property may have plant and shelter resources that are lacking in your space. Bees constantly move beyond the confines of our fence lines so imagine what we could accomplish if we all added a few native plants to our personal and municipal spaces. Working together, as native bee enthusiasts, gardeners, and entire communities, we can create larger, healthier, and more diverse habitats for our tiny cohabitants.

Resources

The Alberta Native Plant Council (ANPC) has a downloadable list of province-wide suppliers of native plants and seeds. You can find the Native Plant Source List on their website.

The Edmonton Native Plant Society (ENPS) website has guidelines on planting native plants and how to grow them from seed. Highlight the Native Plant Sources tab on their homepage to find out more. Plant sale dates and locations for this year have not yet been confirmed, but you can check the website and the ENPS Facebook page for updates.

Purchasing native plant seedlings or plugs will get you started faster and is a more reliable means of adding native plants to your landscape. Growing native flowers from seed can be an exercise in patience as germination can be inconsistent, and you generally won’t get flowers until the second year. If you want to grow your own native plants from seed, Giant Hyssop (Agastache foeniculum) is a good choice to begin with.

For further reading about plants native to Alberta and making your landscape more bee-friendly, consider the following books:

100 Plants to Feed the Bees: provide a healthy habitat to help pollinators thrive. Xerces Society.

Go Wild! With Easy to Grow Prairie Wildflowers and Grasses by Cherry Dodd and the Edmonton Naturalization Group

Native Plants for the Short Season Yard: best picks for the Chinook and Canadian Prairie zones by Lyndon Penner

NatureScape Alberta: creating and caring for wildlife at home by Myrna Pearman and Ted Pike